Château Gaillard

Château Gaillard

We're traveling downstream along the Seine river

through Claude Monet country.

He was born in Paris in 1840 and the family moved to

Le Havre at the mouth of the Seine in 1845.

Then he moved to Paris in 1857 and stayed with an aunt.

After a year in the army in Algeria,

study of art in Paris, marriage, and a year in

London and Zaandam to avoid the Franco-Prussian War,

he and his wife moved to Argenteuil,

now an industrial northern suburb of Paris but

then outside the city.

They lived there from December 1871 to 1878.

In the summer of 1878 they moved to

Vétheuil.

His wife died there in 1879.

Monet stayed until 1881, moving then to Poissy

with his children and their caretaker,

whom he later married.

In May 1883 the Monet household moved to Giverny,

where he lived until his death in 1926.

We have been in

Haute-Isle

and

La Roche-Guyon,

and we are now traveling north on the

D 913 highway.

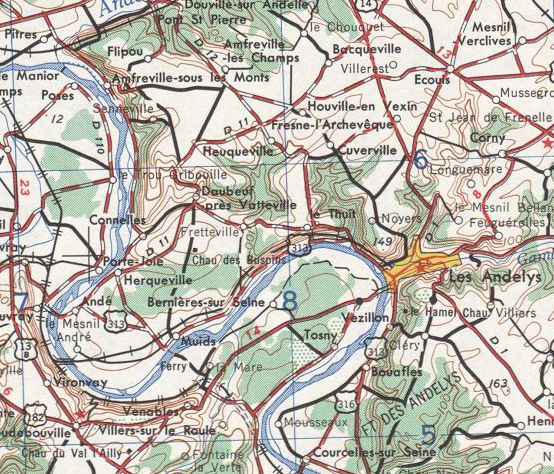

(The D 913 was #313 when this 1953 map

was created).

We're approaching Les Andelys.

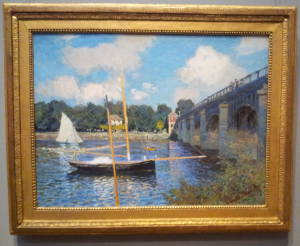

Claude Monet's Argenteuil (1872) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Amazon

ASIN: B00N4P9WY8

Claude Monet's The Bridge at Argenteuil (1874) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Amazon

ASIN: 0300083491

Long Before Monet

This was the land of Claude Monet and Impressionism in the late 1800s into the 1920s, and Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) also painted here, but this area has been occupied since prehistoric times. This area on the right bank of the Seine, to its north, was the home of the Gaulish Veliocasses people. The Romans called them the Veliocassinus, and this led to the area being called Vexin.

The Norse nobleman Hrólfr (or Rollo, ca. 846–ca. 932) was the first ruler of the Viking-controlled territory that became Normandy. He made several incursions into the western half of the Vexin. The Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte in 911 established the Duchy of Normandy and defined its border with the Kingdom of France, splitting the Vexin in half as the Vexin normand and Vexin français.

Then William of Normandy, a Duke and therefore supposedly subordinate to the King of France, led the invasion in 1066 that conquered England. This gave him the throne of England and the same ranking as the King of France. The Duchy of Normandy had suddenly become a continental part of the Kingdom of England.

The Vexin was a heavily contested border region during the twelfth century, lying between the areas controlled by the Angevin Kings of England and the Capetian Kings of France. This area was of strategic importance, close to Paris and on the Seine river water route to the Normandy coast.

Anjou was a county, it was ruled by a man ranked as a Count in the hierarchy of European nobility, starting around 880 AD. It was centered around the city of Angers in the lower Loire river valley. During the ten years from 1144 to 1154, two successive Counts of Anjou gained control of a large region of what today is France. A big part of this happened when the French King Louis VII divorced Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1153. Henry of Anjou immediately married her, and the couple now controlled the southwestern quarter to third of what today is France. The King of France really controlled just the small Île-de-France region surrounding Paris, and his "control" of that required the cooperation of the various Counts and other nobility running things at the local level.

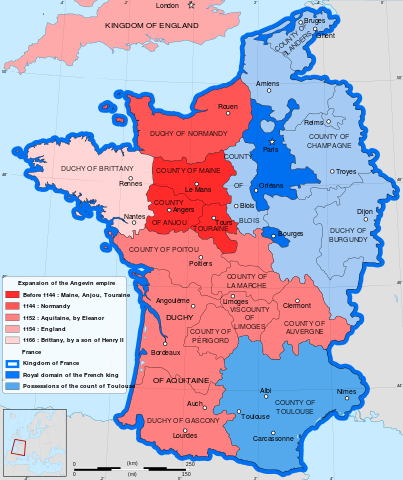

Angevin territory shown in shades of shades of red, map from Wikipedia

In 1154 Henry, the Count of Anjou and husband of Eleanor of Aquitaine, also inherited control of Normandy and the throne of England. He became the English King Henry II. About half of the territory of today's France was now controlled by the King of England. Henry and his two successors, Richard I and John, were known as the Angevin kings.

The name of the Angevin dynasty or royal house came from their origins in Anjou. Historians in the late 1800s started calling the Angevin territory in England and the continent the "Angevin Empire", but at the time no one thought to call it that. Those kings simply thought of it as their possessions. Of course it was simply the territory that belonged to them.

Henry II and Thomas Becket

Henry II had rapidly risen in position from Count through Eleanor's Husband to King. He had to struggle to gain real control of some of the areas within his domain. The Archbishop of Canterbury died in 1162, and Henry appointed his friend Thomas Becket to replace him. Henry hoped that he could now control the church in England. Becket, however, decided that the king had appointed him as Archbishop to get things done, and so he would really take charge of the church.

Becket was heavy-handed at times, and his biggest problem as Henry saw it was that he wasn't simply a yes-man for the king. Their disagreements over the rights and privileges of the church led first to legal fights, and then to Becket being exiled for five years.

After his return from exile, Becket went back to exercising control of the church. When Henry's heir apparent was crowned at York, instead of Canterbury as usually done, Becket excommunicated the three clergymen involved — the Archbishop of York, the Bishop of London, and the Bishop of Salisbury. The three of them fled to Normandy, where Henry was. Meanwhile, Becket continued to excommunicate his opponents.

When the three clergymen told him what had happened, Henry said, "What miserable drones and traitors I have nurtured and promoted in my household who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk." Then he supposedly said, "Who will rid me of this troublesome priest?"

The "dog whistle" isn't a recent invention of politicians wanting to win the support of racists and other bigots without the inconvenience of explicitly saying anything offensive. Henry might have been blowing a dog whistle, or maybe he had no idea what would come of these remarks.

On 29 December 1170 four knights went to Canterbury Cathedral. They had gotten Henry's message whether he really intended it or not. They stashed their weapons outside under a tree and put on cloaks to hide their mail armor. The entered the cathedral, found Becket, and told him that he had to go to Winchester and explain his actions to the king.

Becket refused, so they went out to retrieve their weapons and hurried back in with drawn swords.

Gruesome popular accounts aren't a recent invention of Quentin Tarantino or the grindhouse films he references. The appropriately named Edward Grim, who was wounded in the attack, wrote this lurid description:

The wicked knight leapt suddenly upon him, cutting off the top of the crown which the unction of sacred chrism had dedicated to God. Next he received a second blow on the head, but still he stood firm and immovable. At the third blow he fell on his knees and elbows, offering himself a living sacrifice, and saying in a low voice, "For the name of Jesus and the protection of the Church, I am ready to embrace death." But the third knight inflicted a terrible wound as he lay prostrate. By this stroke, the crown of his head was separated from the head in such a way that the blood white with the brain, and the brain no less red from the blood, dyed the floor of the cathedral. The same clerk who had entered with the knights placed his foot on the neck of the holy priest and precious martyr, and, horrible to relate, scattered the brains and blood about the pavements, crying to the others, "Let us away, knights; this fellow will arise no more."

Becket was immediately venerated as a martyr and he was put on the fast track to sainthood. He was canonized as a saint in February 1173, just over two years after his death. In July 1173, Henry made a public penance, walking barefoot to Canterbury Cathedral and being scourged there by monks. He also visited the church of Saint Dunstan's, which became one of the most popular pilgrimage destinations in England.

The four knights had fled north to Knaresborough Castle in northern Yorkshire for about a year. Henry did not have them arrested, and did not confiscate their property, but then he didn't help them when they asked for assistance. The Pope excommunicated them. They went to Rome to ask for forgiveness, and the Pope sent them off to fight in the Crusades in the Holy Land for fourteen years.

Things never went well for Henry II. Squabbling within the family led to multiple armed rebellions. Chosen heirs died of dysentery and tournament accidents. Henry died in 1189. On the day his third son, Richard, was crowned as his successor, there was a mass slaughter of Jews. Things in the Kingdom of England were a horrible mess.

Map of Britain and France in 1190 from the Perry-Castañeda Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin. If you asked the King of France, his kingdom was accurately labeled on this map as all the light purple territory in today's France and Belgium. But the reality was that the Angevin King of England controlled everything west of the dotted border line running roughly north-south between Rouen and Paris, between Tours and Orléans, and curving east almost to the territory of the Holy Roman Empire. (which was neither Holy, nor Roman, nor truly an Empire, and which is shown in blue here)

Amazon

ASIN: 1445662701

Amazon

ASIN: B001NVIZ3E

Richard Lionheart

Richard was born and grew up in England, but once he was crowned King of England he spent almost no time there, possibly only about six months in total.

Richard got things into reasonable order during the first year of his reign, and then he took off for the Third Crusade in the Holy Land.

On the positive side, he became known as Richard Cœur de Lion or Richard Lionheart for his military bravery and leadership.

But on the other hand, he massacred 2,600 prisoners at Acre, deposed the King of Cyprus and sold the entire island, insulted various other royal leaders, and supposedly arranged for the 1192 assassination of Conrad of Montferrat, the King of Jerusalem and ruler of the Crusader States. Two Hashshashin stabbed Conrad on his way home from having dinner with a friend, one attacker was killed and the other captured. Under torture, the surviving Hashshashin said that Richard was behind the assassination. Who knows, torture reliably yields confessions but it's pretty useless for getting accurate information.

Richard had planned to become King of Jerusalem once Conrad was out of the way, but that didn't work out. Then, traveling in disguise on his way home from the Crusades, Richard was captured and imprisoned by Leopold V of Austria. Leopold was Conrad's cousin, and Richard had already insulted Leopold and refused to share his spoils from the Crusade. Maybe that's why Richard was traveling in disguise.

Leopold handed Richard Lionheart over to Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Duke of Bavaria, possibly figuring that two guys named Lion-something deserved each other's company. Henry the Lion got in touch with England, at that point under the control of Richard's brother John, who had taken over Richard's unattended English holdings and let Normandy fall to Phillip II of France. Richard's ransom would cost 150,000 Marks. John imposed a 25% tax on goods and income to raise the money, making himself even less popular in England than he already was. Hence the legend of Robin Hood.

Richard Lionheart Fights Phillip II of France for Normandy

John raised the ransom, Henry the Lion released Richard Lionheart, and Richard returned briefly to England. He got back in charge of affairs in England, forgave John, and quickly left England for the last time in 1194. Over the next five years, 1194-1199, King Richard Lionheart of England fought King Phillip II of France for control of Normandy.

Richard had recaptured much of Normandy by 1196. Richard and Phillip II negotiated the Treaty of Louviers in January 1196. According to this, neither king was allowed to build any fortification at the site of Andely manor on a defensible outlook overlooking the Seine above the town of Grand Andely. The manor was controlled by the Archbishop of Rouen as it belonged to that diocese.

Later in 1196 Phillip began besieging Aumale in Normandy. Richard ignored the treaty and pressured the Archbishop of Rouen to sell him the manor. The Archbishop wouldn't sell it, as it was one of the church's few remaining profitable properties.

Richard soon seized the manor, regardless of the treaty or the church's unwillingness to sell. The manor was on a high point 90 meters above a bend in the Seine, and this would be an excellent location for a fortress.

Construction started immediately and proceeded rapidly. Richard spent an estimated £12,000 building what came to be called Château Gaillard. During his entire reign he spent only £7,000 on all castle construction in England, so this was a huge project. The outer walls were 3-4 meters thick, enclosing an area about 200 by 80 meters.

Château Gaillard was mostly completed by 1198, and it became Richard's favorite residence in the final year of his life. He issued official documents designated "apud Bellum Castrum de Rupe" or "at the Fair Castle of the Rock".

This was an early example of concentric fortifications. Earlier castles were usually one wall around a large central space, with one or more towers on the wall and one or more moats or ditch-and-bank rings outside. This castle had three concentric enclosures separated by dry moats, with its keep or donjon within the innermost enclosure.

It was one of the first European castles to have machicolations, projections at the top of the walls from which you could drop rocks or other objects on assaulting forces. The outer faces of the inner bailey walls were covered with near-hemispherical projections, reducing the damage from siege engines as almost all projectiles hit a surface at a glancing angle.

It's thought that Richard picked up design ideas from castles he had seen in Syria during the Crusades.

The town of Petit Andely was built directly below the castle at the same time, now it and the older Grand Andely farther up the side valley are known as Les Andelys.

In 1199 Richard was fighting in the southwest, in Limousin, toward Aquitaine. He was hit by a crossbow bolt. The wound became septic and he died there. Some of his lower digestive tract is buried in a church there, his heart is in Rouen Cathedral, and the rest of him is buried at Fontevraud Abbey near Saumur.

John succeeded his brother Richard in England and Normandy. Brittany, Anjou, Maine and Touraine chose Richard's nephew Arthur as their leader. Phillip II of France supported Arthur's claim to the English crown in order to destabilize the Angevin territory on the continent.

Arthur was murdered, allegedly by John, and John's following actions drove many of the barons in Normandy and other Angevin territory to go over to the side of Phillip II of France.

The fighting went on. John now was really the King of England and not just occupying the throne while his brother was off at the Crusades or in a German prison.

The Siege of Château Gaillard

King John of England was pretty hapless at home and abroad. Phillip seized a number of smaller English fortifications in the area, isolating Château Gaillard.

The local English forces saw that the French army would soon be there, so they destroyed a bridge across the Seine. When the French arrived, they constructed a pontoon bridge allowing their army to move and supply itself.

Two English forces set out to relieve the castle, one moving up the Seine by boats to destroy the floating bridge and the other moving overland to attack the French forces under cover of darkness. Neither part of that plan succeeded. That left Phillip's forces free to begin their siege of the castle in August 1203.

The French started with the classic incendiary weapon of Greek fire, a mixture of naphtha (generally speaking, some flammable liquid hydrocarbon mixture), pine resin, quicklime or calcium oxide (the ignitor, as it releases a lot of thermal energy when it reacts with water), calcium phosphide or Ca3P2, sulfur, niter or saltpetre (potassium nitrate, KNO3), and other ingredients. It had been developed by the Byzantine Empire in the 670s.

The Greek fire let the French seize some of the outer defenses and fully isolate the castle. Now they could dig their own defensive trenches and set up their siege engines. Those started launching large rocks at the castle.

Much of the local population had sought shelter in the castle but now it was a worse place to be. Phillip allowed groups of them to leave from time to time. That let the limited supplies in the castle last a little longer, but still it was just a matter of time.

John sent some raids to Brittany in hopes of drawing some of the French forces away and breaking the siege, but that did not work. John gave up and returned to England, and the defenders were left to do whatever they could to survive through the winter of 1203-1204. Meanwhile the French were building mobile structures to protect their men who would attack gates and walls.

And why does General Motors name an enormous Cadillac vehicle after a nearly suicidal method of fighting on ladders?

The final assaults started in February 1204. The siege engines and archers were barraging the walls with rocks and arrows. Miners were tunneling to damage the walls from below. Escalade was the most fundamental castle assault method: have foot soldiers carry ladders to the wall and try to climb up and fight before the defenders can tip the ladders over or drop some of the heavy rocks lofted into the castle by the siege engines.

The outer bailey finally fell after long fighting and high casualties on both sides. Château Gaillard had multiple concentric rings, so seizing the outer bailey meant that the attackers now had another fortified wall to assault, and another after that.

Garderobehistory

Some of Phillip's men climbed up the garderobe, the drainage chute below the toilets typically built into the perimeter walls of a castle. They let the French forces through that wall into the central bailey. Then there was a dry moat leading to the inner bailey, seen below. A natural rock formation provided cover for the assault on the last gate, and the French took the inner bailey. The English forces surrendered on 6 March 1204.

Phillip pushed on through the remaining English territory, taking Rouen and continuing to the coast. Normandy was now directly ruled by the French King for the first time since 911, when it had been granted to Hrólfr or Rollo. This led to the establishment of absolute monarchy in France, with the King of France really controlling territory that was growing to include today's nation of France.

John had lost all his continental holdings outside of the Duchy of Guyenne (a fragment of Aquitaine), and the Kingdom of England was now restricted to territory on the island of Britain. This weakened John's authority at home. That led to the Magna Carta, which established common law and limited royal power.

Château Gaillard was the home of the exiled David II of Scotland in the mid-14th century. It then changed hands several times during the Hundred Years' War which really lasted a little longer than that, from 1337 through 1453. Henry V of England took Rouen and the rest of Normandy in 1419, but his forces failed to capture this castle. Other English forces did, then the French, and then the English again. Toward the end of that, the French king captured the fortress from the English for the last time.

Amazon

ASIN: B00OCFHHOQ

Amazon

ASIN: B00DQN6IOK

The next and final stop in this series of pages is Rouen, where Richard's heart is buried in a cathedral that Claude Monet painted over thirty times in varying seasons and light.