Aleppo — From Turkey into Syria

Entering Syria at Aleppo

I went to Turkey for an extended trip. The plan — to the extent that I had one — was to travel east from İstanbul to Cappadocia and Nemrut Dağı. Then, from there, generally make my way back west to southwestern Turkey, visiting Ephesus again before returning to İstanbul and flying back home.

I was hoping to visit Syria, but I was not sure that it would work out. The trick was to get a visa. The details are in the later page on logistics, but I got one. After a few days seeing the great sights in İstanbul, I headed east with a Syrian visa. It was good for 14 days out of a 31-day period.

As planned, I spent several days in Göreme, seeing Cappadocia, then took a bus further east to Malatya to go up Nemrut Dağı. Along the way I had met a couple of girls from New Zealand, they were also heading into Syria and so we joined up.

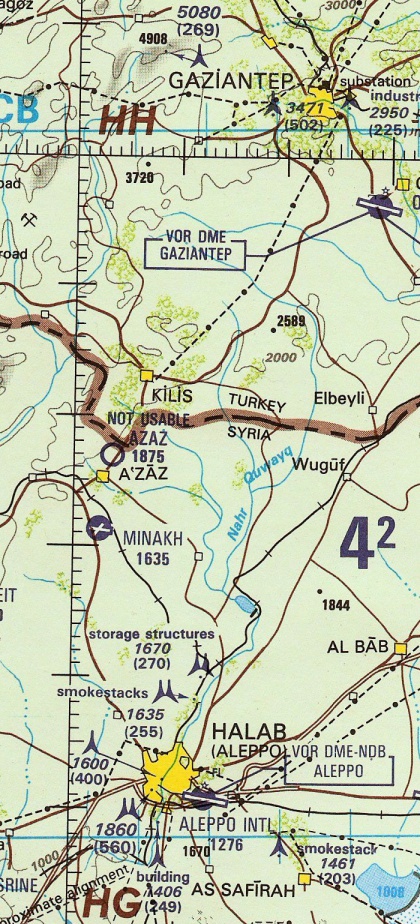

We were leaving Gaziantep in the middle of the afternoon. Looking back, that wasn't the best plan. There wasn't a bus south to the Syrian border as the bus companies said that the border would be closed. But a dolmuş was leaving. A Turkish dolmuş is a shared van, a van or minibus with bench seats. It has no fixed schedule, it leaves when it's full enough. You pay by passing your cash forward to the driver or someone sitting in the front and handling the payments. The cost of the ride depends on how far you're going.

A U.S. Government chart showing Gaziantep, Kilis, the Turkish-Syrian border, and Aleppo.

There was a dolmuş leaving for Kilis, on the Syrian border just south of Gaziantep and north of Aleppo. We strapped our packs to the roof and got in.

The village of Kilis was a few kilometers short of the border itself, but a guy with a pickup truck was heading that way, or at least he was willing to for a little cash.

The border crossing itself was a little bleak, two government blockhouses separated by about 500 meters of no-man's land. Lots of formality and passport and visa checking in the Turkish one, then a pickup truck ride to the Syrian side for further formalities.

Now what?

There's nothing but farmland and a small village on the Syrian side....

One of the Syrian border guards negotiated a ride for us with an older guy who had an immaculate 1950s DeSoto. It was just US$ 15 for the three of us for the 60 kilometers from there to Aleppo. Many classic U.S. automobiles are still on the road in Syria.

American classic cars on the streets in Syria.

Now, on the way across Turkey I had been thinking that venturing into Syria was somewhere between risky and stupid. I was from the U.S., so this was surely going to be unpleasant. Endless hassles, I figured, the locals wouldn't want me there. But I supposed that I could put up with just about anything for twelve to twenty-four hours. I would be in Aleppo, a major city just across the border. If it was too unpleasant then I could spent one night, at the bus station if necessary, and head back across the border the next day.

But was I ever wrong....

As for the name of the place: Aleppo is an Italianized version. It was known in antiquity (and it's been settled for about 7,000 years) as Khalpe and Khalibon, and the Greeks called it Beroea. The name Alep started being used during the Crusades. Halaba is Aramaic for "white" and might refer to the light soil and abundant marble in the area. The Arabic name for the city is Halab, or 'ħalab for the full orthographic version. Another theory is that Halab comes from "gave out milk" and refers to the tradition that Abraham, who is thought to have lived around here, gave milk to travelers passing through the area. The Turks, who ruled this area as part of the Ottoman Empire from 1516 until the Empire collapsed around World War I, called it Halap. I found that the locals use a mix of Halab and Halap and they will know what you mean if you ask about Aleppo.

Welcome to the horrible mess of transliterating Arabic into some other script....

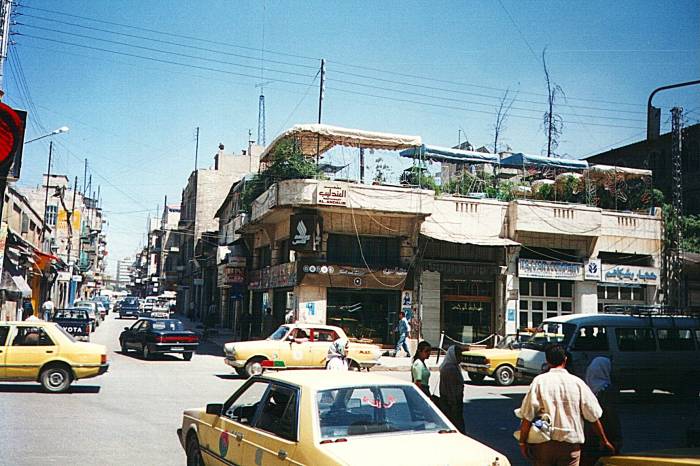

Arrival in Aleppo

The driver dropped us at the main bus station. In the first half block we passed a couple of soldiers who smiled and said, "Welcome to Syria!"

Not at all what I expected...

A few times in Syria I was told something like, "Well, our governments don't really get along," but that was always followed with, "But you, you are welcome to Syria!" Almost everyone was delighted, and often very surprised, to learn where I was from. The biggest hassle was that my attempts at tourism were always getting interrupted with endless small glasses of tea and sometimes being taken to meet the cousin who had never even seen such an exotic creature as an American. It's just added bonus tourism, seeing barber shops and luggage stores and women's shoe stores and other places I wouldn't have seen otherwise.

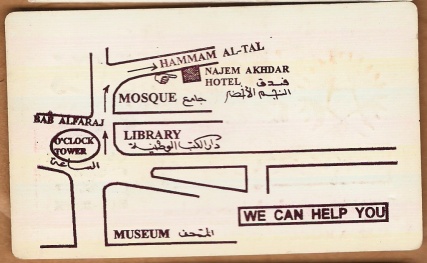

We checked a few of the low-end hotels along Al-Maari between the bus station and Bab al-Faraj. Apparently the Russian prostitutes had the same issue of Lonely Planet, as most of those places were brothels.

We continued down Al-Maari to the clock tower. Facing the clock tower, as seen in the picture below, a Russian / Armenian bazaar district is ahead and to your right. Continue the direction the street sweeper is traveling, past the classic American 1950s car and the red truck, and into the roofed-over street beyond.

Another American classic car passes the clock tower on Al-Maari street near the Russian and Armenian bazaar.

Entrance to the Hotel Najem Akhdar, under the yellow sign.

Signs for: Sawas clothing store, Универмаг Афамя, or Univermag Afamya, and Hotel Nejm Ilahdar. They're stacked in the opposite order in the building.

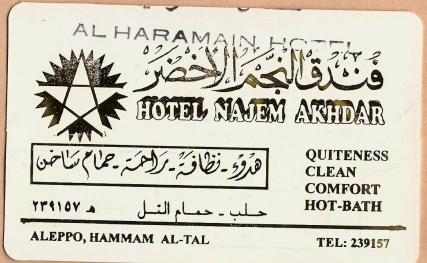

As for a place to stay in Aleppo, the Hotel Najem Akhdar, also known as the Hotel Nejm Ilahdar, can't be beat. 400 S£ (US$ 10) for a double with sink and shower, 250 S£ (US$ 6.25) for a single with sink, shower, and toilet. It's at Hamman Al-Tal (in the Russian / Armenian bazaar), phone +963-21-239157.

Go down the first alleyway to the right of the clock tower. About 30 meters past where it is partially roofed over, turn onto the first real alleyway to your right. About the third doorway on the right (behind the white truck in this picture, these directions have you walking toward the camera viewpoint) opens into a hallway. That leads to a staircase with an Armenian clothing store, the Универмаг Афамя, or Univermag Afamya, on the first floor up. The hotel is above that.

As you see in these signs, there's quite a bit of Russian spoken and written in Aleppo, in addition to Armenian. Many Armenians ended up in Aleppo after the end of the Ottoman Empire, and then the dissolution of the Soviet Union brought more Armenians plus people from many other former Soviet republics. There's more on the languages in the later page on travel logistics.

If the Najem Akhdar is full, they'll direct you to the Hotel el-Sharq. It's a little dodgey, but it may be the only thing available if you show up late in the day. 200 S£ (US$ 5) for a bed in a shared room.

By the way, the usual procedure in Syria is that you must register your passport at the hotel. This will take a while, but you will have some hot sweet tea to sip while doing the paperwork and chatting with the proprietor. Then they will tell you that they must hold onto your passports, "In case the police come". If you tell them that it's OK to wake you if the police come, they let you keep your passport. The police never seem to come to count passports.

Hotel Najem Akhdar business card, stamped where I picked this up at the Al Haramain in Damascus. See the map on the reverse side.

Hotel al-Sharq. Yes, it's adjacent to the Фабрика Готовой Одежды, the Ready-to-Go Clothing Factory.

A view across Aleppo from my room at the Hotel Najem Akhdar. The Citadel is off to the right, the Hotel Baron is nearby to the left.

Aleppo Sights and History

It wasn't too far from our hotel in the Armenian bazaar to Baron Street, and then the Hotel Baron. It's a famous and historic place from the early 1900s. Before World War II, the guests were mostly British (archaeologists, writers, and spies) and Germans (generals and railway engineers).

Agatha Christie stayed there, her novel Murder on the Orient Express opens at the hotel. Lawrence of Arabia, David Rockefeller, and many others also stayed at the Baron.

The Baron is an interesting place to look around. Sit in the overstuffed old leather chairs in the cool bar with its shuttered windows. Take in the W. Somerset Maugham atmosphere, and sip your gin as the Empire falls. Ottoman, British, French, whichever Empire you care to reference.

Athens to Parisby Train

Back in those days Aleppo was the eastern end of the Orient Express. This was the real Orient Express and not these luxury special trains irrelevantly labeled as such. For the full run you would leave London for Dover on a train, where you would cross the English Channel on a ferry. At Calais, on the far northern coast of France, you would board a train made up of sleeper cars. From there it was southeast across Europe and down the Balkan peninsula to İstanbul. Then across the Bosphorus by ferry, and into another train to cross Turkey to Antakya, and across the Syrian border to end at Aleppo.

Agatha Christie's book starts in Aleppo and follows some of the reverse route, the main part of the story taking place between İstanbul and somewhere in today's Serbia.

For the best meals I've had in the Middle East, and maybe the best meals I've ever had on the road, go to the Al-Andalib restaurant in Aleppo. It's on the rooftop at the south-east corner of the intersection just north of the Baron Hotel on Baron Street.

The great al-Andalib rooftop restaurant.

Syrian cooking tends to be very good, and the Al-Andalib is outstanding even beyond Syrian high standards. Just go hungry, as the dinners are huge. The fixed meal one evening started with a large array of meze, or appetizers, which could have been a large meal by itself. This was thin unleavened bread cut into wedges, with:

- Tahini, or sesame-seed paste.

- Hummus, or chickpea paste with tahini.

- Mtabel, a.k.a. baba ghanouj, an eggplant paste with tahini.

- Yoghurt with cucumber slices.

- Hot peppers.

- Diced cucumber and tomato salad.

- Olives.

After all that, a double chicken kebap each!

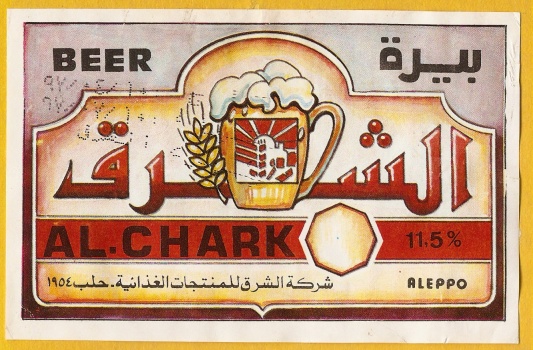

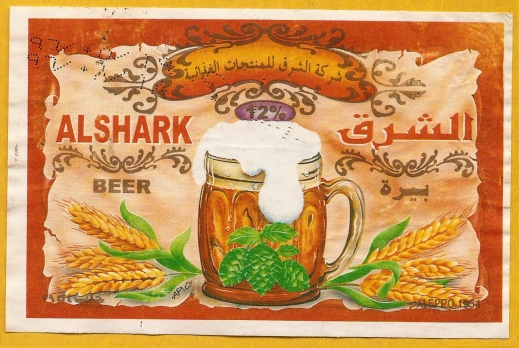

This was accompanied by Al-Chark beer, our first introduction to this somewhat mysterious Syrian beverage. It's all named The East, variously spelled al-Chark or al-Shark or al-Sharq, but the labels are always completely different.

If you buy several of the 330 ml bottles at a time for a group, you will notice that no two hold exactly the same amount. The bottles are a mix of clear and brown glass. Maybe 25% of them have labels, and those label designs vary widely.

And what's up with the "11.5%" and "12%" marking? It certainly isn't alcohol content, which is probably 4% to 5%. The mysteries of "The East"... It seems like the product of a loose consortium of home brewers.

What? Beer in the Middle East? Sure. This isn't Saudi Arabia. And 30% or more of the population of Aleppo is Christian.

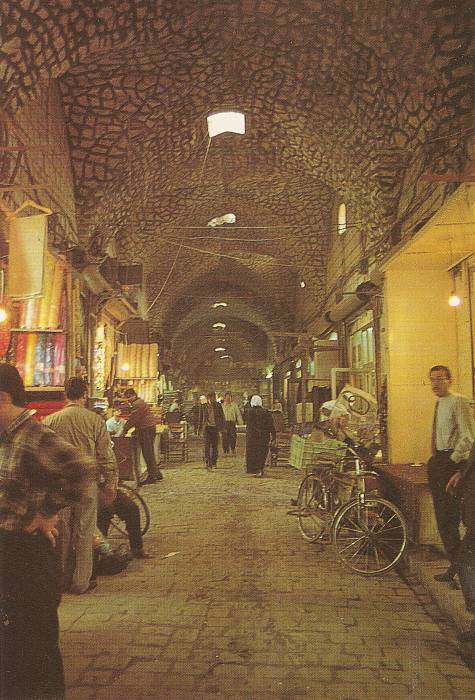

Arched passageway in the Aleppo bazaars.

Another Aleppo suq passageway. This is a scan of a postcard.

Aleppo has the best bazaars of the Middle East, in my opinion. Bazaar, or in Arabic, suq, souk, however you want to spell it.

They're better than either İstanbul or Cairo for that Indiana Jones feeling.

Aleppo has been a major trading center since before history started being written down, and its souqs are really something. A large district at the heart of the old city is a maze of narrow alleyways and aisles between ancient buildings. Over the centuries they put out awnings, then connected the awnings, then built archways, until today the buildings are all interconnected and the alleyways are all covered with arched stonework. It's above ground, but you feel like you're in a basement maze.

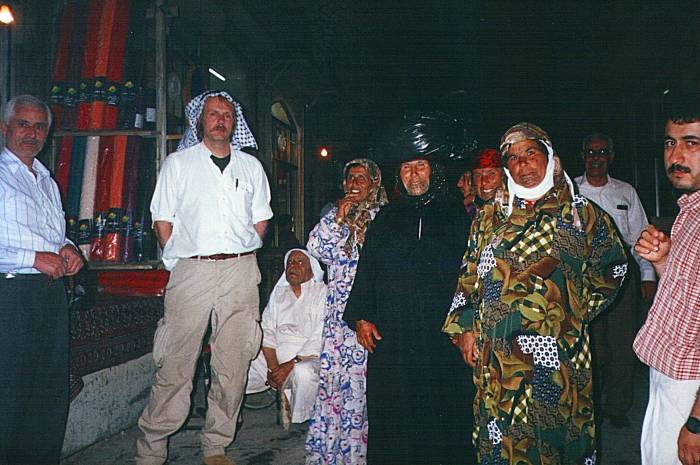

There are people on donkeys, bicycles, mopeds, ancient motorcycles with sidecars, 3-wheeled bikes pulling trailers, and tiny mini-trucks, all weaving through the crowds walking down the narrow passageways. There are women in western dress, women with tattooed faces, women with scarves and veils covering the lower half of their face, and Saudi-style women draped entirely in black so you can't tell which way they're facing if they don't move. Men similarly range from western business suits to robes with kafiyyeh and 'aghileh, the checkered head cloth and black cord. There are dark, lean Bedouins, and redheads that show the remnants of Crusader and French genes.

Clusters of stands and shops specialize in carpets, bolts of cloth, silk scarves, sheep entrails, plumbing fixtures, soap and toothpaste, rope and string, brooms and mops, sponges, and so on. I had thought that the market districts in İstanbul were really something, but the Aleppo souk made that look tame and westernized.

We didn't need any spool of wire or goat skins or light bulbs, but we did buy some of the great custom fruit juice. You find fruit juice stands all through Syria, with a jumble of string bags of fruit hanging from the ceiling and all around the doorway. You can get the default mix, or specify your own. Oranges, grapefruit, bananas, apples, carrots, mangos, etc., whatever you want is sliced up and put into the blender. That is mixed with ice shaved from a large block, and the concoction is poured into a large glass mug.

In the silk traders' bazaar in Aleppo.

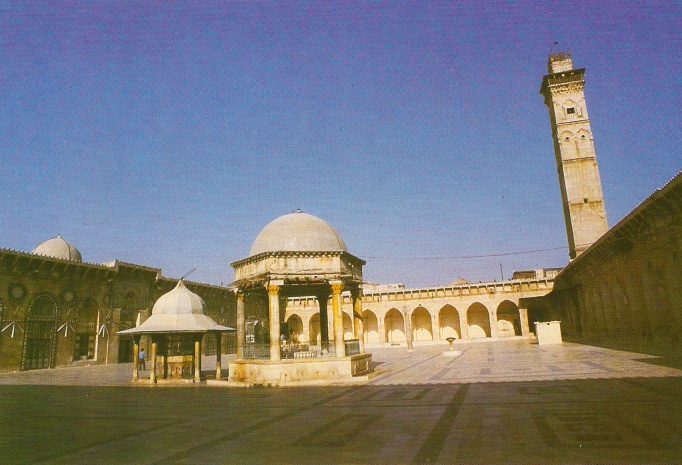

Jami' Bani Omayya al-Kabir, or Mosque of Zachariah or Jami'a Zakarihheh. This is a scan of a postcard. They used a fisheye lens, the tower isn't really tilted!

Another very interesting sight is the Great Mosque of Aleppo, or the Jāmi' Bani Omayya al-Kabīr, founded around 715 AD by the Umayyad caliph Walid I, built on a pre-existing Christian church, itself probably built on an even earlier religious temple.

The mosque contains a tomb said to be of Zachariah, the father of John the Baptist, and so it also gets called Jami'a Zakarihheh or Mosque of Zachariah. As we'll see even more in Damascus, the figures of Christianity are also highly respected figures of Islam. The short version of Zachariah's story is:

Zachariah and his wife are old and childless.

The angel Gabriel tells Zachariah that they will

have a child.

"Yeah, right" says Zachariah.

"I'll show you," says Gabriel.

"You're now unable to speak.

You won't be able to speak again until

Elizabeth has the kid and names him 'John'."

Lesson: If angels tell you absurd things, just nod and accept it.

The main entrance of the medieval Citadel. Scan of a postcard.

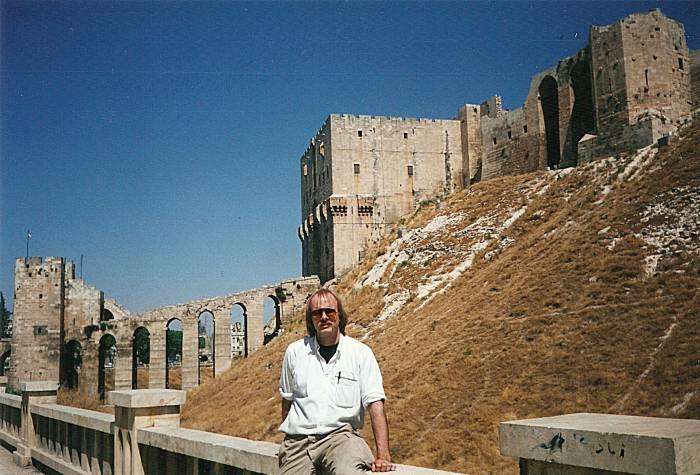

Me at Aleppo's medieval Citadel. The Citadel structures seen here date from the 1200s, although the site has been used for 5000 years.

The story of Zachariah, from the first chapter of Luke's Gospel (Luke 1:5-65). This is a contemporary English translation, so as to annoy the American fundamentalists who think the Bible should be rendered in the Shakespearean English that they think that Jesus spoke, with a pro-slavery Confederate accent.

In the days of King Herod of Judaea there lived a priest called Zachariah who belonged to the Abijah section of the priesthood, and he had a wife, Elizabeth by name, who was a descendant of Aaron. Both were upright in the sight of God and impeccably carried out all the commandments and observances of the Lord. But they were childless: Elizabeth was barren and they were both advanced in years.

Now it happened that it was the turn of his section to serve, and he was exercising his priestly office before God when it fell to him by lot, as the priestly custom was, to enter the Lord's sanctuary and burn incense there. And at the hour of incense all the people were outside, praying.

Then there appeared to him the angel of the Lord, standing on the right of the altar of incense. The sight disturbed Zachariah and he was overcome with fear. But the angel said to him, "Zachariah, do not be afraid, for your prayer has been heard. Your wife Elizabeth is to bear you a son and you shall name him John. He will be your joy and delight and many will rejoice at his birth, for he will be great in the sight of the Lord; he must drink no wine, no strong drink; even from his mother's womb he will be filled with the Holy Spirit, and he will bring back many of the Israelites to the Lord their God. With the spirit and power of Elijah, he will go before him to reconcile fathers to their children and the disobedient to the good sense of the upright, preparing for the Lord a people fit for him."

Zachariah said to the angel, "How can I know this? I am an old man and my wife is getting on in years."

The angel replied, "I am Gabriel, who stands in God's presence, and I have been sent to speak to you and bring you this good news. Look! Since you did not believe my words, which will come true at their appointed time, you will be silence and have no power of speech until this has happened."

Meanwhile the people were waiting for Zachariah and were surprised that he stayed in the sanctuary so long. When he came out he could not speak to them, and they realised that he had seen a vision in the sanctuary. But he could only make signs to them and remained dumb.

When his time of service came to an end he returned home. Some time later his wife Elizabeth conceived and for five months she kept to herself, saying, "The Lord has done this for me, now that it has pleased him to take away the humiliation I suffered in public."

[... Skipping over verses 26-56, in which Gabriel drops in on Elizabeth's cousin Mary to tell her about a baby ...]

The time came for Elizabeth to have her child, and she gave birth to a son; and when her neighbours and relations heard that the Lord had lavished on her his faithful love, they shared her joy.

Now it happened that on the eighth day they came to circumcise the child; they were going to call him Zachariah after his father, but his mother spoke up. "No", she said, "he is to be called John."

They said to her, "But no one in your family has that name", and made signs to his father to find out what he wanted him called.

The father called for a writing tablet and wrote, "His name is John." And they were all astonished. At that instant his power of speech returned and he spoke and praised God. All their neighbours were filled with awe and the whole affair was talked about throughout the hill country of Judea.

The Citadel is one of the oldest and largest castles in the world. The Citadel hilltop has been occupied since at least the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, when it held a temple to the ancient storm god Hadad or Adda. The prophet Abraham is said to have kept his sheep there. It's old.

Archaeology magazine had an article in its Nov/Dec 2009 issue (vol62 no6) about recent discoveries within the Citadel, see "Temple of the Storm God". Worship of the storm god Adda dates back at least to 2400 B.C., when the rulers of the prosperous city of Ebla made the 55 km pilgrimage to the temple.

What you see today of the Citadel is mostly from the Ayyubid period in the 1200s AD. And all this gets into the deep history of Aleppo:

~5000 BC — The Aleppo area is settled, as found by excavations at the nearby Tallet Alsauda. It became the capital of the kingdom of Yamkhad.

~1600—800 BC — The ruling Amorite Dynasty was overthrown and the city came under Hittite control, ruled from their capital at Hatuşaş at today's village of Boğazkale in Turkey.

~800-333 BC — The area was in the Assyrian and Persian empires.

333 BC — Captured by the Greeks under Alexander the Great. This is when it was renamed Beroea, after a city in Macedonia, Alexander's home country.

64 BC — Conquered by the Romans.

637 AD — Fell to the Arabs under Khalid ibn al-Walid.

944 — Became the seat of an independent Emirate.

962—987 — Sacked by a resurgent Byzantine Empire in 962 and became an Ottoman Imperial vassal.

1000 — Fatimid conquest and start of the Byzantine-Seljuk wars.

1009, 1124 — Besieged but not captured by Crusaders. This is when it came to be called Alep.

1183 — Came under the control of the Ayyubid Dynasty.

1260—1400 — Taken by the Mongols under Hulagu in 1260. Fought over and variously controlled by the Mongols and the Mamluks.

1516 — Became part of the Ottoman Empire.

1603—1606 — Aleppo is mentioned by Shakespeare. In Macbeth the witches torment the sea captain of the Tiger, headed from England to Aleppo but enduring a 567-day voyage before being forced back to port. The final words of the title character of Othello are, "Set you down this / And say besides that in Aleppo once / Where a malignant and turbanned Turk / Beat a Venitia and traduced the state, / I took by th'throat the circumcised dog / And smote him — thus!"

1918 — The Ottoman Empire fell apart with the end of World War I. Today's Syria became a large part of what was called the French Mandate, a colony of France, until World War II (1939-1945).